Are there Slums in Beijing?

Mike Davis’ book Plant of Slums (2006) examined the rapid urbanization that started in the late 20th century and how neoliberalism contributed to both urbanization as well as the growth of slums in the global south. As countries in the global south decolonized, the mechanisms of imperialism became more insidious. Termed neocolonialism, this new form of colonialism worked through predatory economic policies as well as through military might. The World Bank and Internal Monetary Fund lend money to developing nations, with high interests rates and insist on "structural readjustment programs." These programs meant privatizing large portions of the economy, and as a result, agriculture moved from subsidence farming to cash crops owned by multinational corporations. Since living off of agriculture became more difficult, more of the global poor moved to large cities where multinational corporations build factories. Even with new manufacturing plants coming in, these cities could not provide enough income for all the newcomers and as a result, people started to squat and slums were built.

In chapter 3, Davis (2006) goes into the history of why urbanization was slow in the first wave of colonization. When imperialist nation held direct colonial rule over the third world, they would oppress peasant populations harshly, sometimes only allowing them to temporarily migrate to large cities when there was a lack of labor. Likewise, in Stalint (i.e. authoritarian communist) regimes, such as Maoist China, they at first allowed post-revolutionary peasant soldiers to move to the city to look for work but as cities became crowded, the regime started to limit internal migration. According to Jeffery Wasserstorm and Maura Elizabeth Cunningham, in China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know (2018), after the market reforms in the post-Mao era, development required more labor than what was available in the cities. The availability of more jobs, plus the development of formally rural areas lead to mass migration into cities.

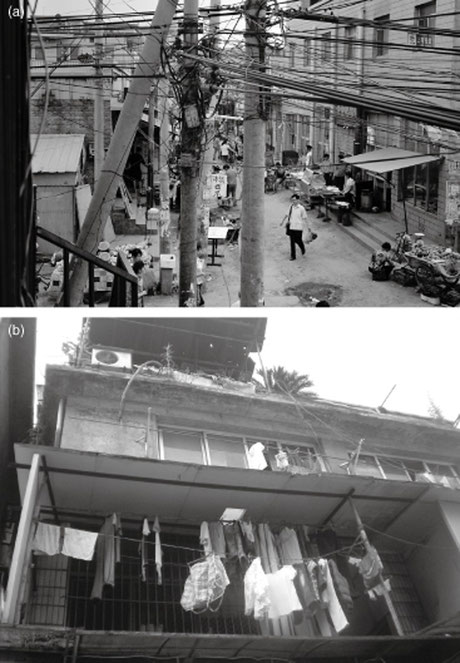

Rural exodus has led to an increase in informal housing for the poor in both urban and rural settings, including in Beijing and the suburbs of Beijing. But there was a unique quality to Beijing's slums, for example, Daniel Goodkind and Loraine A. West (2002) called them "floating populations" because they often lived in precarious situations and were often forced to relocate as the city is developed. They also experienced hardships due to the PRC's welfare system called hukou - a welfare system that only gives benefits people who remain where they were born. This welfare system was instituted during the Mao era in order to control the movement of the population. Since the market reforms of the 1980s, the CCP has recognized that they need rural workers to come into the cities to help with development, yet they have not done away with hukou's restrictive policies.

According to an article in Newsweek by Elanor Ross (2017), Beijing city authorities found approximately 400 people living in "basements of high-end residential and office" buildings." These rooms had no windows and had 36 beds in one shared living space. Most of the people living in rooms were migrant workers who went to the city looking for work, but they were unable to afford apartments because the rent in Beijing is approximately 1.2 times their monthly wages. According to research by Annette M. Kim (2016), there were approximately a total of 1 million people in Beijing living in similar conditions. Some of them living in basements, others living in bomb shelters. Although these living conditions were extreme, the total population for Beijing was 23 million people, and one million people living in such situations has failed to capture attention from both scholars and policymakers. Indeed, compared to the five to six million people living in Beijing's urban villages, one million does not seem like a lot.

According to research by Zhigang Li and Fulong Wu (2013), urban villages were formerly rural villages that get incorporated into larger cities and then converted into informal rental housing, also occupied by migrant rural workers. Urban village occupants were more family oriented than people who live in formal housing. While most urban village dwellers have a stable income, most of them do not have secure contracts with their landlords.

Community organizing and protests have been rare for slum dwellers, according to a Wall Street Journal article by Eva Dou (2017). Yet in late 2017, as Chinese officials were evicting migrant workers out of informal houses in response to a deadly fire in a slum. Middle-class professionals, as well as U.S. and European embassies, felt that these the CCP was using the fire as an excuse to control the population of migrant working class and called the forced evictions "human rights violations." This outrage led to demonstrations in Beijing. These demonstrations lasted several hours until the police ordered them to disperse.

The PRC's neoliberal reforms put Chinese workers in a precarious situation. Rapid urban development created a demand for unskilled workers in Beijing, yet the PRC's restrictive welfare system and migration controls make it incredibly difficult for the Chinese migrants to make a living in the city. This situation leads to the development of a slum population called "floating populations."